|

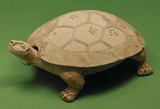

Chinese (Han dynasty) Tortoise-Shaped Inkstone 206 B.C.-A.D. 220 Gray earthenware 4 inches high, 10 inches long William Hood Dunwoody Fund 32.54.4a,b |

The

tortoise-shaped inkstone is a ceramic sculpture made in China during the

Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220). Like the later Tang dynasty, the Han

was an era of peace, prosperity, and stability. Han leaders built on the

unification of the country begun by China's first emperor, Shi-huangdi,

from the preceding Qin (chin) dynasty (221-206 B.C.). They further expanded

the empire and established a well-organized bureaucratic system that lasted

for two thousand years. Their control of most of central Asia led to the

opening of the Silk Road, a five-thousand-mile network of caravan and

sea routes reaching all the way from China to Imperial Rome.

The

tortoise-shaped inkstone is a ceramic sculpture made in China during the

Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220). Like the later Tang dynasty, the Han

was an era of peace, prosperity, and stability. Han leaders built on the

unification of the country begun by China's first emperor, Shi-huangdi,

from the preceding Qin (chin) dynasty (221-206 B.C.). They further expanded

the empire and established a well-organized bureaucratic system that lasted

for two thousand years. Their control of most of central Asia led to the

opening of the Silk Road, a five-thousand-mile network of caravan and

sea routes reaching all the way from China to Imperial Rome.

Most surviving Han ceramic sculptures were made for burial in the tombs of people at all social and economic levels. This inkstone is a rare discovery; very few tortoise figures have been found among tomb objects. Principal Han ceramics include jars and lamps of many shapes, often decorated in LOW RELIEF, and mortuary figures of men, women, animals, houses, and animal pens. Early tomb figures from the Western Han (206-about 100 B.C.) depict military figures and life at court. Popular subjects include dancers, acrobats, and musicians performing at banquets and festivities for the nobility. By the time of the Eastern Han period (A.D. 25-220), all burial pottery consisted of objects from the daily life of the common people,1 such as everyday pots, models of stoves, well heads, granaries, pigsties, and houses and many other domestic items.

The Han believed that humans were made up of three parts. When the body, or xing, died, the soul separated into the po and the hun. After death, the po stayed with the body, while the hun went to paradise. The tomb was furnished with ming ch'i, goods to accompany the dead in the afterlife and serve the future needs of the po. Tomb goods indicated the life and social position of the deceased and provided familiar objects and comforts. The inkstone identifies the tomb inhabitant as a Chinese scholar, who would have used it as one of his tools for writing.

The demand for tomb furnishings increased regard for ceramic products, which until this time had been considered inferior to objects made of bronze.

Notes

1. S. J. Vainker, Chinese Pottery and Porcelain: From Prehistory to the Present (New York: George Braziller, 1991), p. 40.

Key ideas.

Where does it come from?

What does it look like?

How was it used?

How was it made?

Discussion questions.

Additional resources.

Select another piece.