Alcohol in the 1700s Atlantic World

In 2017, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) reinterpreted four period room suites as part of its “Living Rooms” initiative.1 The installation in the historic c. 1735 Parisian Grand Salon, “Up All Night in the 1700s,” addressed nightlife, card-playing, and the consumption of imported stimulants: coffee, tea, and chocolate.2 It did not address alcohol. This collaborative initiative attempts to address that omission. It began with a question: what alcoholic drinks would have been served at an eighteenth-century Parisian house party?

Particularly one hosted by Jean Gaillard de la Bouëxière, the original owner of Mia’s Grand Salon and a fermier général, or royal tax collector. The answer soon emerged: wine and its sweeter, distilled relative, brandy.3 These grape-based tipples were also top taxable commodities and a massive source of revenue for the French economy—not to mention Gaillard de la Bouëxière’s bank account. One could say his salon—a room designed for entertaining—was, fittingly, built with wine.

What alcoholic drinks would have been served at an eighteenth-century Parisian house party?

Around the same time, a few steps away from the Grand Salon—but worlds away, culturally—the austere Providence Parlor was reinvigorated with an installation, “Just Imported: Global Trade in 1700s New England.”4 This historic interior originated in the 1772 Rhode Island property of the Russell brothers, who sold goods imported at their store, The Sign of the Golden Eagle.5 An interactive station at the center of the room displays samples of the kinds of wares they sold, all gleaned from the Russell brothers’ newspaper advertisements.6

Amid the assortment is a bottle of rum from the British island of Jamaica. But New England rum also shared a surprising connection with the “grape lobby” of Gaillard de la Bouëxière’s world. Slaveholding French and British Caribbean plantations were leading centers of rum production where, right next to the sugar cane fields, the juice and molasses cast off in the sugar-refining process were collected and distilled to make rum.

Through these period rooms we get a glimpse of the complex geographies of alcohol and their tangled histories in the 1700s Atlantic world.

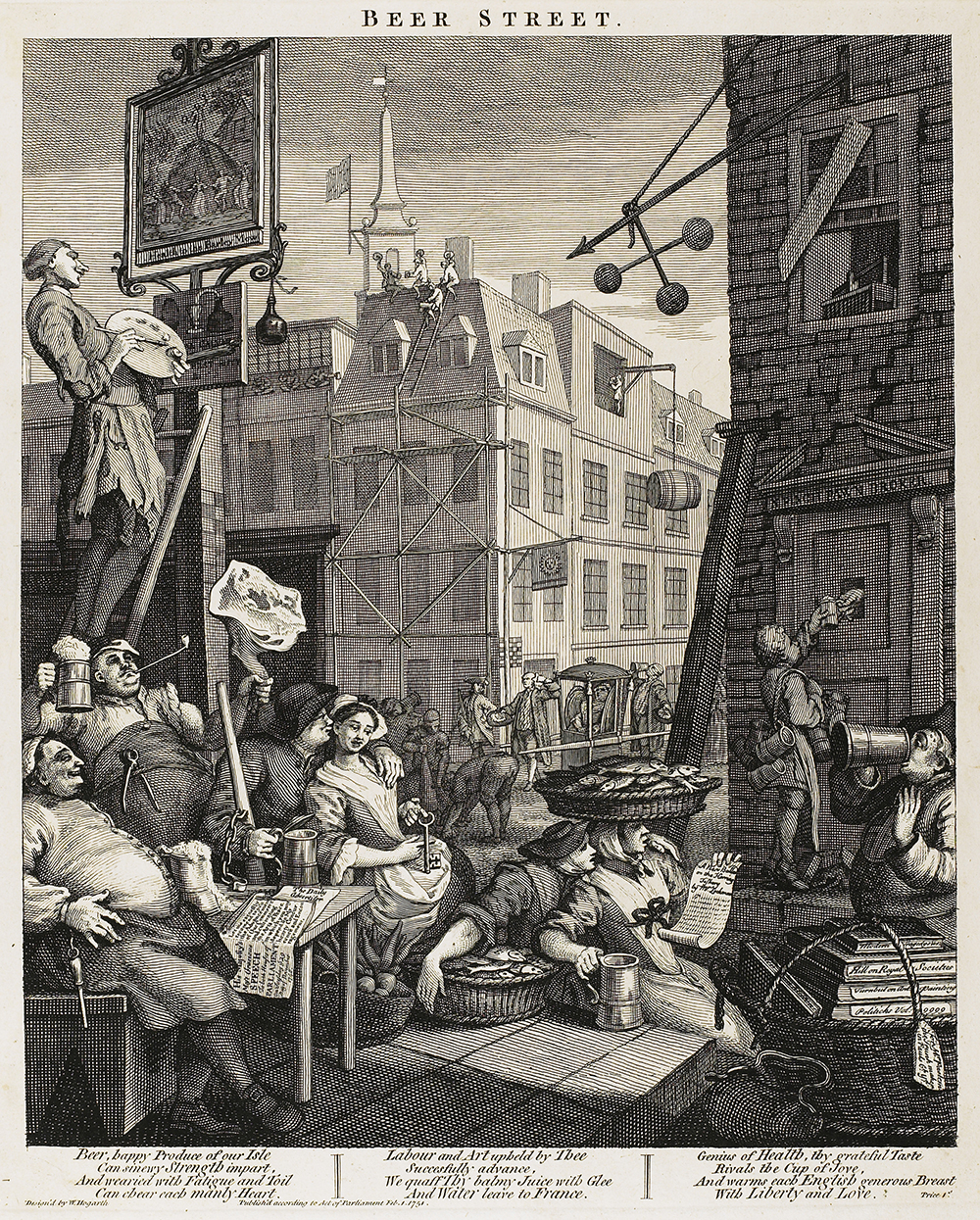

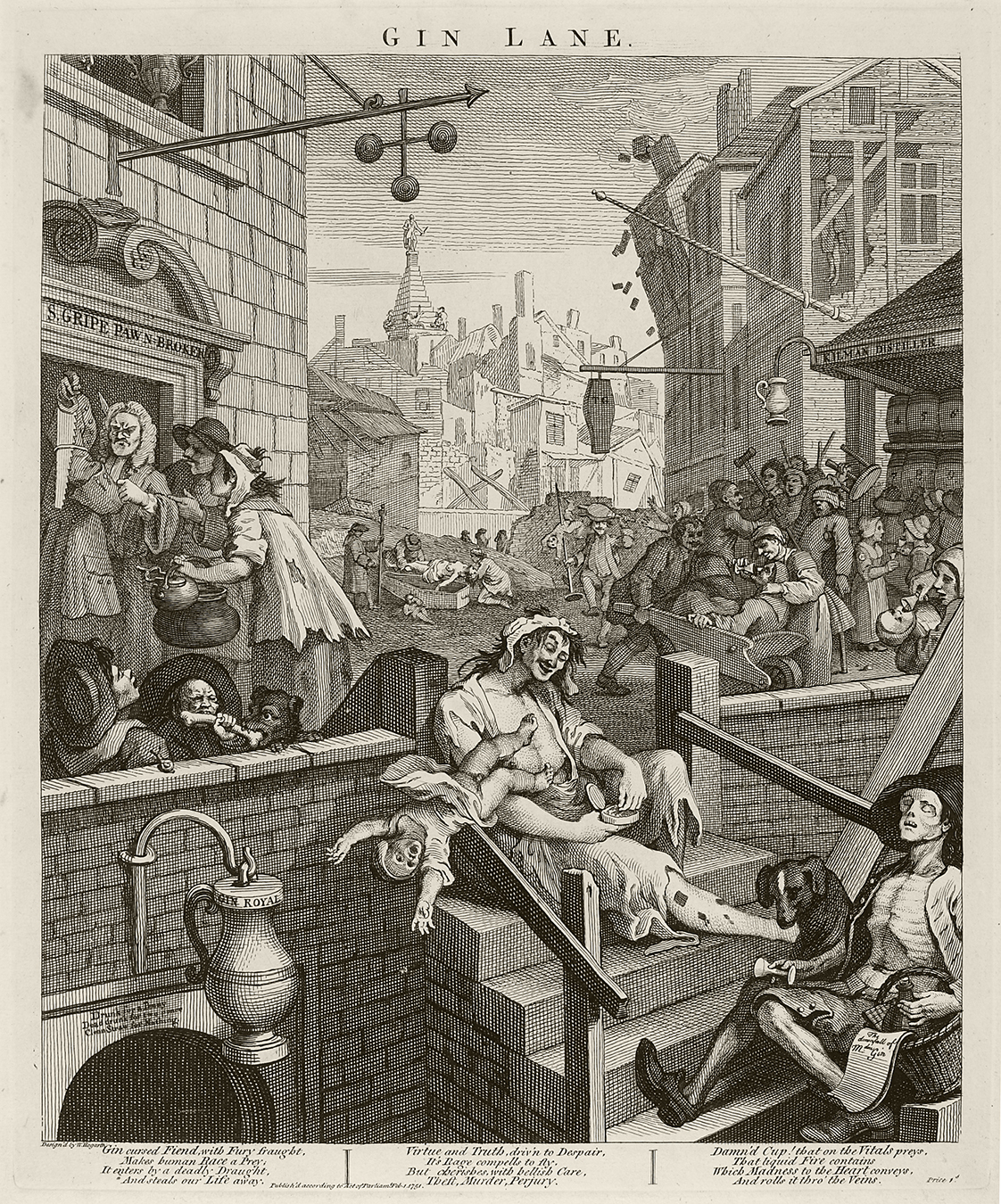

While Britain—which had no major alcohol industry, except beer and, later, gin—welcomed rum into its ports, in 1713 the French government formally prohibited both the production of French rum and its import into France or French colonies in a move to protect domestic wine and brandy makers.7 However, there is evidence that French Caribbean rum (known as tafia) was illicitly produced and traded in modest quantities, making its way to French Canadian territories, African slave-trading ports, and in numerous other sites in the Atlantic world. But, more importantly, French West Indies sugar planters sought ways to commercialize their molasses by-products and found crucial outlets in British New England, where the local rum industry flourished thanks to the influx of cheap French molasses.

The map below, dating from 1797, highlights the indigenous and colonial powers of North and Central America and across the Caribbean islands.8 Use the tool to zoom.

Through these period rooms we get a glimpse of the complex geographies of alcohol and their tangled histories in the 1700s Atlantic world.

View in Collection (Click here to zoom.)

The Herschel V. Jones Fund, by exchange, Minneapolis Institute of Art

View in Collection (Click here to zoom.) The Herschel V. Jones Fund, by exchange, Minneapolis Institute of Art

During this century of colonization and globalization, new drinks like rum grew out of intensifying systems of forced labor, along with new global commodities, like sugar.9 Enslaved Africans on Spanish plantations in today’s Dominican Republic likely first experimented with fermented sugar-based alcohols in the 1500s, as they sought methods to make something similar to the palm wine of their homelands. (Spain, also home to thriving wine and brandy industries, eventually made rum manufacture illegal in its American colonies.) It is also possible that prototypical rum production diffused into the Caribbean northwards from Brazil, where the Portuguese dominated global sugar production by 1600. At the same time, increases in long-distance shipping drove the demand for distilled spirits because, with their much higher alcohol content, spirits did not spoil as easily as beer or wine, and sailors relied on alcohol as part of their rations. But colonial powers, with their distinct cultural attitudes and economic anxieties surrounding old, new, and emerging strains of alcohol, both fueled and thwarted the global distribution of alcohol in different ways.

Notes

- “Living Rooms: The Period Rooms Initiative,” Minneapolis Institute of Art, Accessed November 13, 2018, https://new.artsmia.org/living-rooms/ ↩

- “Up All Night in the 1700s,” Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Accessed November 13, 2018, https://new.artsmia.org/living-rooms/up-all-night/ ↩

- Noelle Plack, “Intoxication and the French Revolution,” Age of Revolutions, December 5, 2016, https://bit.ly/2zOK7o1 ↩

- “Just Imported,” Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Accessed November 13, 2018, https://new.artsmia.org/living-rooms/just-imported/ ↩

- Matthew Powers, “Joseph and William Russell House,” Clio, Last Updated September 7, 2018, https://www.theclio.com/web/entry?id=65325 ↩

- Carl Robert Keyes, “March 19,” The Adverts 250 Project, March 19, 2018, https://adverts250project.org/2018/03/19/march-19-3/ ↩

- Melvyn Bragg (host), “The Gin Craze,” In Our Time, BBC Radio 4, August 9, 2018, https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/in-our-time/id73330895?mt=2&i=1000417483717 ↩

- Kitchin, Thomas, Kitchin’s General Atlas, describing the Whole Universe: being a complete collection of the most approved maps extant; corrected with the greatest care, and augmented from the last edition of D’Anville and Robert with many improvements by other eminent geographers, engraved on Sixty-Two plates, comprising Thirty Seven maps., Laurie & Whittle, London, 1797. Source: Wikimedia ↩

- Bertie Mandelblatt, “Trans-Imperial Geographies of Rum: Production and Circulation,” Age of Revolutions, November 28, 2016, https://bit.ly/2fxNNmT ↩