|

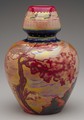

Zsolnay Ceramic Factory Pécs, Hungary Vase About 1906 Porcelain with luster and other glazes Designed by Sándor Hidasy Pilló or Terez Mattyasovszky 12-3/4 inches high, 9-3/4 inches in diameter Gift of the Decorative Arts Council 94.36 |

In his efforts to create more artistic ceramics, Vilmos Zsolnay became absorbed in the production of reduced-pigment luster glazes. The technique had been used prior to the seventeenth century in creating Islamic, Spanish, and Italian majolica but was subsequently lost. The refound glazes were the result of Zsolnay's lengthy scientific experimentation in collaboration with Vince Wartha, a chemistry professor at the Technical University of Budapest.

In this process, after two firings, the surface of the pottery is painted with a compound of silver or copper oxide and then fired a third time at a lower temperature. The pots are not placed in protective SAGGERS, so when wood is added to the kiln, the carbon monoxide of the smoke combines with the oxygen in the metal oxides. The resulting REDUCTION causes the oxides to partially crystallize and leave a thin layer of metallic deposits on the surface of the vessels. After cleaning, silver oxide produces an IRIDESCENT yellow-gold luster, while red to warm golden-brown tones result from the copper oxide.

The brilliant Eosin, or "sunrise," glaze used on this vase was first developed in 1893 and became Zsolnay's most innovative, celebrated technical accomplishment. A rich ruby-red luster was the most difficult color to achieve. Iridescent colors, like metallic red Eosin and deep blue Labrador, established Zsolnay as a leader in the production of art pottery. Critics who viewed these works at the international expositions recognized an Oriental influence that evoked the rich, shimmering colors of Byzantine and Turkish art.2 The complexity of these glazes has made them difficult to define technically today.

Many Zsolnay pieces were one-of-a-kind art objects. In cases where multiple copies were made, artists prepared colored design sheets and skilled artisans executed the designs on the vessels.

Notes

2. Alfredo Melani, "Hungarian Art at the Milan Exhibition," International Studio 29, no. 116 (October 1906), p. 306.

Key ideas.

Where does it come from?

What does it look like?

How was it used?

How was it made?

Discussion questions.

Additional resources.

Select another piece.